The Marriage of Data Exfiltration and Ransomware

Over the past two months, two types of cyber extortion, Ransomware and Data Exfiltration, have been combined to further complicate the lives of victims. In order to understand where this may be going, it is worth reviewing how we got here.

Historical Basis of Data Exfiltration Extortion

Prior to Q4 of 2019, data exfiltration extortion events were not nearly as prevalent as ransomware. We estimate that less than 5% of enterprise cyber extortion incidents involved data exfiltration and it was extremely rare to see the two methods of extortion combined. A typical data exfiltration extortion typically involved a black hat group or lone individual exfiltrating a large amount of data from a company. The exfiltrated data would first show up for sale on forums and dark marketplaces to test the secondary market value. The victim company would often become aware of the breach via threat intelligence feeds, but not always. After the data is monetized, or at least attempted to be sold, the exfiltration group would try to contact the victim and extort them for the non-release of the data. The basis for this is purely to prevent reputational damage on the part of the victim. As the data is already out, the breach cannot be reversed. Victims typically follow a course of first enumerating the data that has been breached to determine notification / disclosure requirements and then make a judgement call on whether to give into the demands of the exfiltration group. The exfiltration groups have a few levers to pull to pressure victims. Threatening the sale of the data is one route, though most victims are counseled that this has likely already occurred. The second is threatening public disclosure of the data, the intent being reputational damage to the brand. The medium used for disclosing breached data is typically the traditional media or public websites or forums. For the most part, journalists will not allow their publications to be leveraged as a platform for extortion, and won’t allow a story about the breach to run when contacted by an exfiltration group. The alternative is posting the data on a public site. Sometimes the data is just posted on a forum to deliberately draw attention, which can then elicit a media response. Sometimes the exfiltration group will actually create bespoke websites to post the data and then add some search optimization formatting to get the pages indexed and ranking in search. Both methods require a great deal of work in order to create leverage on the victim. The mixed success of this type of cyber extortion has traditionally relegated it to a tertiary activity and only carried out under unique circumstances by cyber crime groups that typically did not deploy ransomware.

Ransomware and Data Exfiltration Start to Blend

In the summer of 2019, a forked Hermes variant called DopplePaymer gained momentum. The ransomware was a BitPaymer derivative and utilized a new TOR site to guide victims through the extortion process. The original TOR site (below) did not carry any threats to release exfiltrated data.

Original DoppePaymer TOR Site…before they called it DopplePaymer

Shortly after DopplePaymer was seen in the wild, a different version of the TOR site emerged. This TOR site did threaten the release of exfiltrated data. The HTML on the site showed threatening text, was commented out, indicating that the threat actor groups could toggle this language on or off depending on the victim subject to the attack.

HTML from the DopplePaymer TOR site showing Data Exfiltration Threat

It is possible that this was actually an A/B test to determine if the threatening language led to a higher conversion rate of victims paying. Today, the DopplePaymer sites threatens the release of data as a standard part of all their attacks, as shown on a recent version of their TOR site.

DopplePaymer TOR site as of December 2019

Enter Maze Ransomware

Maze Ransomware Note as of December 2019

Maze ransomware started to show up in various spam and exploit campaigns as early as May of 2019, but it was not until late October that their new tactic of releasing breached data and names really made an impact. In a well publicized incident, the Maze group released the data of a single victim in order to make an example. They then subsequently set up a public shaming board to publicize both the identity of a victim and the data that had been stolen. Maze makes it clear in their ransom notes that they have exfiltrated data and intend you use that as leverage on top of the encryption ransomware. The intent is to increase payment conversion. Many victims of ransomware have adequate backups and never even contemplate engaging with the threat actors, let alone paying them. The threat of public reputational harm is aimed to tip payment conversion higher for the cyber crime groups. Companies are not taking this development lying down though, and ransomware groups that seek public platforms on the internet may find it hard to keep their sites live. This won’t prevent the breached data from becoming disseminated, but will certainly curtail the effectiveness of the reputation damage.

Above is a snippet from a conversation via the Maze TOR site where the threat actor notifies the victim that exfiltrated data has been made public.

Will Other Ransomware Groups follow Suit?

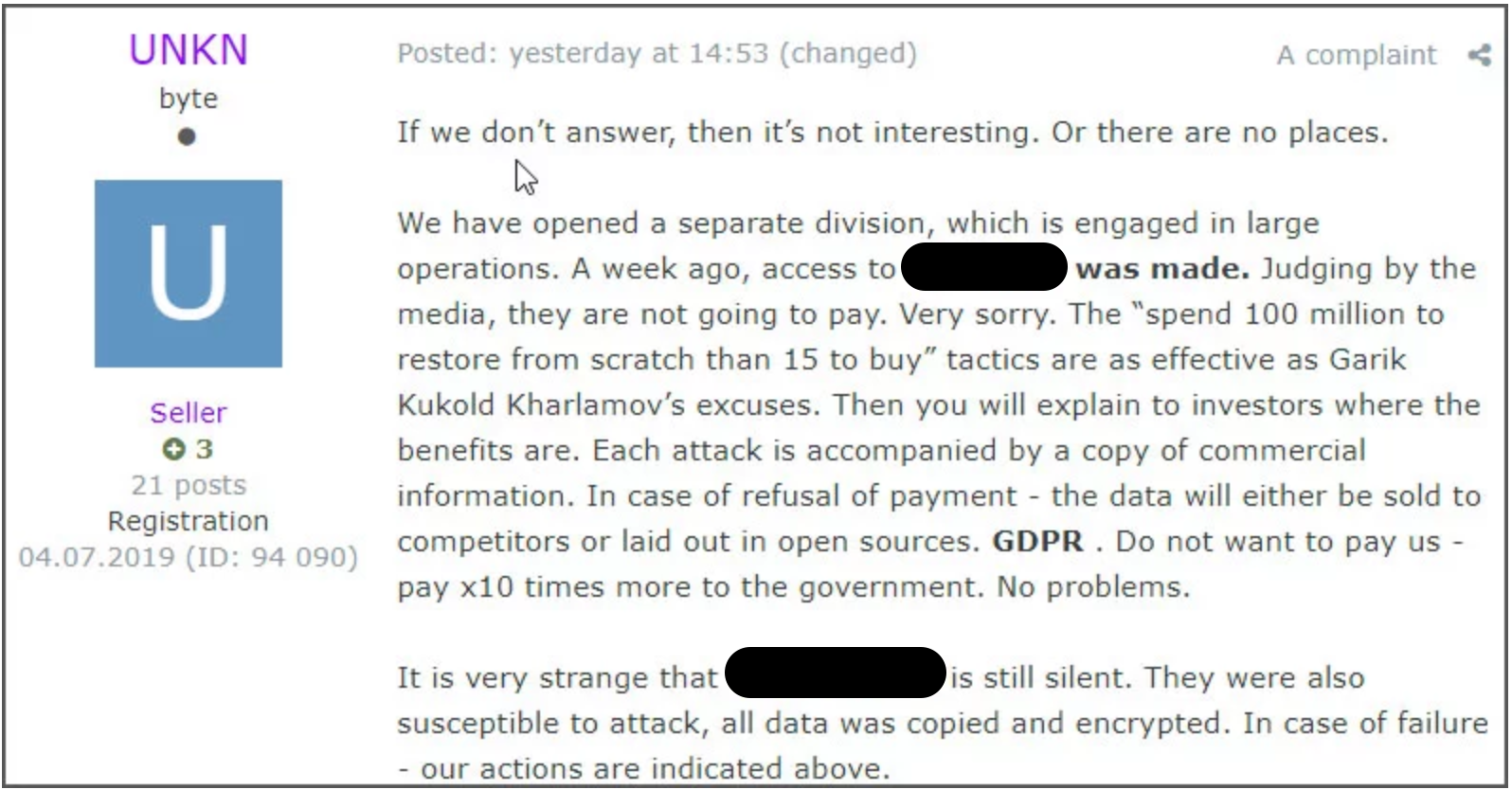

In early December, the Sodinokibi Ransomware group posted on a forum that they intended to follow Maze and others by employing the data exfiltration and public shaming tactic. Sodinokibi has developed a brand through its highly specialized affiliates of attacking Managed Service Providers (MSPs) and encrypting every managed endpoint. A magnification tactic that has led to the collapse of several service providers.

Presumed Sodinokibi actors discuss publicizing exfiltrated data

So far, Sodinokibi has followed through on this initiative. Coveware has validated that Sofinokibi affiliates are exfiltrating data as part of their attacks. To date, no public websites have been created to shame victims that do not pay. While this group is threatening the release of the data, they are not always willing to provide proof that they have indeed exfiltrated data, so it may be a bluff or phantom incident in some cases.

Will This Data Exfiltration / public shaming Tactic Work Long Term?

While it is clear that Maze ransomware has already had some success in converting this new tactic (as evidenced by some company names initially posted to the news site being removed, presumably because of payment), Coveware believes this tactic will actually backfire in the long term for two reasons.

Reason #1 data exfiltration / public shaming will fail: It will have no impact on the response from properly advised companies. When data is exfiltrated it constitutes a breach, regardless of if it gets posted on a public site. Once the data has left the building, companies have notification obligations regardless of where the data goes after it has left their possession. Companies under the advisement of a privacy attorney will make the proper disclosures to affected customers and the appropriate regulatory bodies. The consequences of trying to cover up a breach by paying, only to have the cover up come out later are much worse. As the saying goes, ‘its not the crime, but the coverup.’ It should be assumed that the data has already been sold by the threat actors anyway. The negative press from the breach can only become worse if the negative press includes a coverup. This being said, we don’t expect all victims to self disclose. Some will choose to pay and mitigate potential brand damage.

Reason #2 data exfiltration / public shaming will fail: Shame is a powerful emotion. Unlike a ransomware attack, where the operability and viability of the company are in jeopardy, the threat of public shaming bruises ego’s. While brand damage can be material, it is not nearly as material as business interruption. Moreover, paying a ransom can be done quietly and without public shame (sometimes…). No one wants to pay a ransom, but when faced with the choice of existential downtime, businesses often pay to end the pain. The threat of being shamed publicly evokes a different emotion all together though. Shame can evoke anger and obstinance as a response, not obedience and control as the attackers hope. Additionally, companies facing this threat can mitigate the effects by taking the responsible / high road (notify law enforcement, make the required notifications and disclosures, vow to make security amends) and can even win applause by stating they WON’T give in to cyber extortion by paying. While the affected parties may be bothered by the breach, it’s hard to find any fault in that response. Shame is the wrong emotional button for cyber criminals to press. Our bet is that it fails long term.